Female Performance & Health Initiative

Delivering educational opportunities and resources relating to key female athlete performance and health considerations

Athlete stories

Anabelle shares her experiences with her menstrual cycle, hormonal contraception and body image.

Anabelle Smith

Diving

Anabelle shares her experiences with her menstrual cycle, hormonal contraception and body image.

Anabelle Smith was juggling her Year 12 studies and final preparations for her Commonwealth Games diving debut in Delhi in 2010 when, at a pre-event training camp in China, the 17-year-old menstruated for the first time.

“So that was interesting,’’ recalls Anabelle, now 28. “I was away from home, didn’t have my mum around, but thankfully had some older senior athletes to help me out.

“I’ve been pretty lucky that, ever since, my period’s been pretty regular and relatively ‘normal’. But it’s definitely still something I’ve had to monitor - and it’s had its challenges.’’

That has included, at 19, blindly following a doctor’s recommendation to start taking the contraceptive pill in order to manage her menstrual cycle, and enable her to skip a period if it was due to arrive during a competition.

Issue one: the side-effects, including depressed mood and heightened emotions at training. Issue two: severe stomach pains that saw her taken to hospital, where a blood clot was discovered. Anabelle has not taken the pill since.

“Personally, now, I just prefer not to put anything artificial like that into my body, and because I’ve usually had a regular period, it’s been easy for me to work around it, but that’s not always the case for everybody.’’

Nor has it always been so for Anabelle, who has suffered from amenorrhea - or absence of menstruation - a couple of times when her body fat has dipped below what the Rio Olympics bronze medallist now recognises as healthy levels.

She has seen and heard from fellow athletes that failing to menstruate is viewed as a positive because it’s an indicator of weight loss. She knows that is worryingly false.

“As you get older you understand that’s actually really dangerous, and it’s really good that I’ve found the right weight and power ratio that has allowed me to maintain a normal menstrual cycle,’’ says Anabelle.

“But for younger kids it’s a risky area to get into - especially if it’s not monitored and they’re not being honest with their support team. It can take a little bit of time to understand what’s normal and what’s not normal.’’

For half the population, menstruating is what’s normal. So, often, are pre-menstrual symptoms, with Anabelle needing to manage mood swings, fatigue and an increased appetite, but supported throughout by her coach, Andy Banks.

“I can communicate to him if I’m having cramps, or I’m just not feeling energised - he doesn’t ask too many questions, but he understands, and we work around my training program like that,’’ says Anabelle.

“It does become a little bit more stressful if it’s in and around competition … if I know that my period’s going to fall on a competition day, that’s not best-case scenario! My day one might be I’ve got period cramps or stomach pains or whatever, but after that I’m generally fine, so it’s tricky.’’

Which is all part of why education is essential, and the ideal outcome is that this type of story will not be necessary in five years. But, for now, as they say, you don’t know what you don’t know.

This is the time to find out, though, for more girls are reaching puberty earlier, and in aesthetically-influenced sports like diving and gymnastics, sleek swimsuits and leotards mean there is nowhere to hide a changing body composition, however natural that may be.

“I feel for the younger kids, who probably aren’t as comfortable with their bodies and what’s going on, let alone having to be in bathers all the time,’’ says Anabelle, a triple Commonwealth Games medallist on top of her Rio podium finish with Maddison Keeney in the 3-metre springboard synchro.

“It is difficult. A lot of divers start when they’re pre-pubescent and then they go through puberty whilst training and being in bathers, so there is an understanding from coaches and administrators and senior athletes that it’s a normal thing to go through puberty, and it’s a normal thing to gain extra body fat when you’re an adolescent.

“But to go through it yourself can be really challenging. There’s mirrors and people everywhere and your dives are on video.

“I definitely went through those insecurities and being super self-conscious, but it helps once you gather an understanding and appreciation that everyone’s going through the same thing.

“It’s important just having positive role models around who encourage people to embrace their bodies and their differences. But it can be a tough period when you’re still learning that.’’

Emily opens up about managing her menstrual cycle and hormonal contraception while also managing multiple sclerosis.

Emily Petricola

Rowing / Cycling

Emily opens up about managing her menstrual cycle and hormonal contraception while also managing multiple sclerosis.

As tricky as it can be for female athletes - and women in general - to navigate the vagaries of the menstrual cycle, reigning quadruple world champion para-cyclist Emily Petricola faces additional challenges in the week each month that she truly dreads.

Emily, a former elite rower, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis at the age of 27. After seven years without being able to exercise, for even heated swimming pools were too warm, she first jumped on a bike in 2015. At 40, she is now training for the postponed Tokyo Paralympics.

But the debilitating disease that attacks the central nervous system brings other complications. During the week before her period, what Emily describes as her “pretty significant" MS symptoms are at their most severe.

For many, help for premenstrual syndrome comes in the form of hormonal contraception; for Emily, the problem is the fact that the pill can elevate core body temperature by half-to-one per cent.

It may seem trifling, but the physical consequences, especially during vigorous competition in the Japanese heat of August-September, means this champion para-athlete has to look for options elsewhere.

“I just know that one week out of every month, there’s gonna be a lot of trouble,’’ she says. “I’ll be really tired and almost looking for my period to come so I can start to feel better. It’s actually the second day of my period I start to come good again.’’

Just over a year ago, Emily started with Paralympic physiotherapist Keren Faulkner and began an on-off conversation around pre-cooling strategies and trials ahead of a fortnight of competition in Tokyo involving two different track and road events and two types of cycles: the two-wheeled and menstrual kinds.

Various experts agree that the pill is not ideal for Emily, for whom a rise in body temperature exacerbates her existing MS symptoms and leads to a loss of power, function and balance, as well as contributing to more extreme fatigue.

“I’ve got lesions in my brain and my spinal cord, and when I’m hot my core temperature comes up to make those lesions more problematic, so any issues that I’ve had can become more prominent with heat, and that can further compromise my grip and the co-ordination of my left leg so that it becomes really challenging.’’

On the track, the individual pursuit is shorter and thus should be more manageable; the time trial on the road, though, lasts around 40 minutes. Difficult? Very.

Thus, the plan is for an all-progesterone Merina (IUD) to be inserted in April. Emily is a guinea pig of sorts, and happy to be.

So, does she ever wish she was, well, male?

“All the time. Every month!’’ she laughs. "Men have got no idea how much more difficult this stuff is to manage for us!

“It’s really complicated. I’ve coached male and female athletes at a school level (in rowing), and it is something you have to think about - especially when you’re dealing with teenage girls.

“It’s an important area of study and definitely one that needs a lot more emphasis and research and a greater understanding at both the athlete and the coaching level.

“As people go through coaching modules and education from this point forward you would hope it would be part of the way we teach our coaches, because no-one just coaches men or coaches women any more.

“You need to be able to coach both sexes and to be able to do that effectively with females you need to have a really strong understanding of how this can impact any athlete, also know how to deal with any questions that might arise.

“There needs to be a generalised understanding of how the (menstrual) cycle works. But, more than that, coaches also need to be able to pick up on when something isn’t right.’’

Laura was faced with a decision - be an athlete or live a so-called ‘normal’ life.

Laura Harding

Sailing

Laura was faced with a decision - be an athlete or live a so-called ‘normal’ life.

Laura Harding was 16 when she realised that, as she puts it, there was “something a little bit off”. Unlike her friends, she was not menstruating. Never had. Her local GP ordered some basic tests, then told Laura to wait until she was 18.

By then, still nothing had changed for the 2018 world junior sailing champion. During that next consultation, the doctor told her that it was all OK. Just part of being an athlete. Come back when you turn 21.

“But at 19 I was like ‘OK, this really isn’t right’,’’ Laura recalls. “So I went to a female ultrasound place and they basically said ‘you don’t have a uterus’.’’

Really? Could that even be possible? To this day, the Sydney-based Melburnian is yet to meet anyone who has heard of the condition - Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome - that affects just one in 5000 females.

The next step was to work out how, apart from the obvious and distressing reproductive consequences, it would affect her life and what, if anything, could be done.

“I’m still seeking answers, really,’’ says Laura, now 21, a Victorian Institute of Sport scholarship-holder and Australian sailing squad member whose Olympic sights are on Paris 2024 in the International 49erFX Class.

“It was a bit of a shock to the system. I have ovaries, so the only thing that’s different is that I don’t have a period. I assume that I have normal hormone-level fluctuations and that everything else functions the same, but that’s what we’re trying to investigate. It’s a bit of a work in progress at the moment.’’

Laura and the VIS medical team are assessing the impact on training and competition of not knowing - without the usual signs - what stage of the menstrual cycle the young athlete is at in any given time.

They hope to establish a monthly baseline fluctuation level in the young athlete’s hormones to use as a measuring tool, then use the information most advantageously.

“It’s just something to take into consideration; knowing how you’re going to be influenced by certain training days and sometimes you might get some mood swings or be a little bit more frustrated than usual,’’ Laura says.

“I think nutrition is a big part of it as well - knowing how much support your body needs at certain times.’’

Laura is trying to look at the positives - admitting with a laugh that never having a period is one of them. But she gets quietly emotional when discussing the impact of such a rare condition.

“I guess I went through a stage where it was really hard to know what my future was going to look like,’’ she says.

“So experiencing my diagnosis in some ways made me assess what all my goals are in sailing and kind of solidify where I want to take my athletic career and what I want to achieve.

“It was a big turning point in my life where I had to really decide whether I wanted to be an athlete or live a so-called ‘normal’ life.’’

Laura the athlete won. Not for the first time. Or, one suspects, the last.

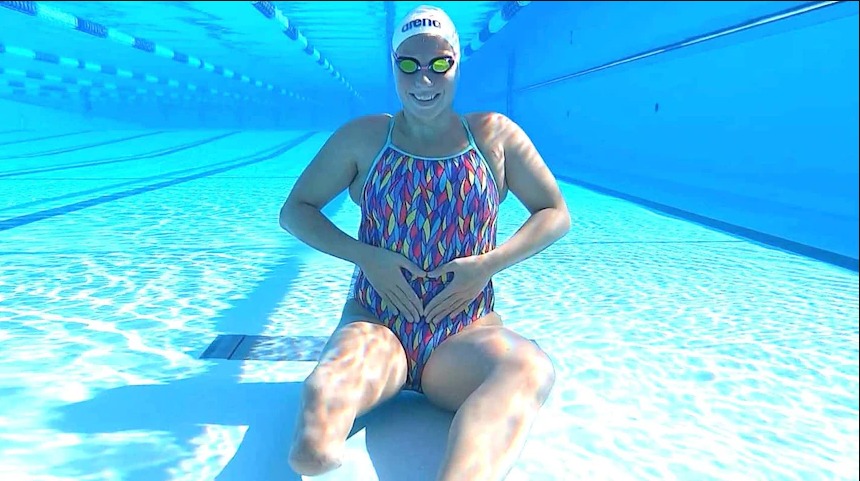

Dual Olympic Kayaker Alyce Wood has helped pave the way for future mum athletes after training up until 39 weeks pregnant before welcoming her beautiful daughter Florence.

Alyce Wood

Kayaking

Dual Olympic Kayaker Alyce Wood has helped pave the way for future mum athletes after training up until 39 weeks pregnant before welcoming her beautiful daughter Florence.

The Paddle Australia medical team supported Wood each step of the way alongside the AIS Female Health & Performance Initiative team who also captured world-leading data.

Paralympic silver medallist Monique Murphy has shed some light on her journey with endometriosis to help other women athletes have a more positive experience.

Monique Murphy

Swimming

Paralympic silver medallist Monique Murphy has shed some light on her journey with endometriosis to help other women athletes have a more positive experience.

Olympic Race Walker Jemima Montag opens up about her nutritional journey as a female athlete and how this has impacted her performance.

Jemima Montag

Swimming

Olympic Race Walker Jemima Montag opens up about her nutritional journey as a female athlete and how this has impacted her performance.